When the Man They Called ‘Hogmeat’ Made Some Super Bowl History

On February 4, 2018, millions of people around the world will watch Super Bowl LII, even though a good many of those millions do not care about American football at all. Whether it is the hyped-up advertisements or just the desire to be at a fun party with free food and drinks, most Americans—and many fans abroad—will tune in to watch the National Football League’s championship game.

Inevitably, Chuck Howley’s name will come up during NBC’s telecast of the game, as it always does. As the big game approaches its end in the late hours of Super Bowl Sunday, modernity once again will test his relevance by asking the random trivia question: Who is Chuck Howley?

He is the only member of the losing team to win the Super Bowl’s Most Valuable Player Award.

It happened on January 17, 1971, as Super Bowl V ended with the then-Baltimore Colts defeating the Dallas Cowboys, 16-13, on a last-second field goal by placekicker Jim O’Brien. But this game was far from “super” as the two teams combined for six interceptions and five fumbles—not to mention 14 penalties, ten on Dallas alone.[i] Baltimore won the game, despite turning the ball over seven times.

As the Colts had no worthy candidates for the game’s MVP Award and the Dallas defense forced those seven turnovers, Howley—playing linebacker and registering two interceptions and a fumble recovery—became part of Super Bowl lore. No other player in Super Bowl V stood as tall as Howley, even in defeat, and this is the only time, still, in Super Bowl history that a player who lost the game won the MVP Award.

Here is how it happened to the man his teammates called “Hogmeat.”

Modern statistical analysis has changed the way we view sports accomplishments of the past, just as any historical framework has done previously. As one modern statistical analysis phrased the challenge, “Defensive MVPs are much less statistically straightforward and must therefore be analyzed on a case-by-case basis.”[ii] The problem with mere statistical interpretation of past accomplishments is the lack of context, but that’s why sports historians exist. We can start with the numbers, but qualitative analysis is just as valuable.

Context is simple here: Super Bowl V was a slop fest of bad football. No player on the winning team played consistently well enough to earn the award, although one could argue retrospectively for Baltimore tight end John Mackey: His second-quarter touchdown reception set a then-record for the longest scoring play in Super Bowl history, and it was the only play that kept the Colts in the game, as they trailed 13-6 at halftime (naturally, O’Brien missed the point-after kick).

However, Mackey’s play was the result of simply being in the right place at the right time on a twice-tipped pass that was not thrown his way.[iii] Plus, he only caught one other pass in the game, an insignificant five-yard reception. As for O’Brien, missing the extra point negated the heroics of hitting the game-winning field goal, and the numerous interceptions and fumbles by the Colts offense meant no other offensive player was going to be considered for the MVP.

Defensively, Chuck Howley accounted for three turnovers in the game. The only other player in Super Bowl history to achieve this was Oakland Raiders linebacker Rod Martin in Super Bowl XV when he intercepted Philadelphia Eagles quarterback Ron Jaworksi three times.[iv] Martin was not named the MVP in Oakland’s 27-10 victory, however, as the Raiders had offensive stars that day. The other nine defensive players since Howley to win the Super Bowl MVP award did not have a hand in three turnovers—although certainly they were a part of dominant defensive efforts that directly impacted the outcome of the game to the point they overshadowed the offensive contributors on their own team.

To address the contextual challenge above, the MVP voters at the time—sportswriters—watched a game that statistical analysis still can quantify today. The fact Dallas was leading the game midway through the fourth quarter meant that with a little less than eight minutes remaining, the Cowboys were in the dominant position to win.

This certainly influenced the thinking of the voters, despite the late comeback and eventual victory by the unimpressive Colts. Both Baltimore scores in the fourth quarter were set up by tipped-pass interceptions,[v] meaning all three Colts scores—including Mackey’s aforementioned touchdown catch—were somewhat “lucky” in the sense that the ball “bounced” Baltimore’s way at the most opportune times.[vi]

The Cowboys lost this game more than the Colts won it. All three interceptions thrown by Dallas quarterback Craig Morton came in the fourth quarter. The Baltimore defense itself did not produce a single performance like Howley’s in its efforts in stifling the Cowboys offense late, either. Three different players intercepted Morton, and the one Colts fumble recovery—a historically noted bad call that never should have happened—[vii] was not the result of anyone’s stellar individual effort. Howley was an obvious choice, statistically speaking—and in context of game flow and (surprising) end result.

Chuck Howley turns 82 years old in June 2018. He was born in West Virginia, attended West Virginia University and was drafted in the first round of the 1958 NFL Draft by the Chicago Bears.[viii] He was traded to the Dallas Cowboys in 1961 and played 13 seasons for America’s Team.

In examining the historical record of Howley’s sporting life, though, one key theme stands out: perseverance. Athletics came easy to Howley, as he lettered in five sports at WVU: football, gymnastics, swimming, track and wrestling.[ix] But when he got to the NFL, Howley struggled in his second season, thanks to a knee injury that almost ended his career.

He took the entire 1960 season off and then made his comeback with the Cowboys. The rest, as they say, is history. Another knee injury, late in the 1972 season, ended his career, as Howley played in just one game in his final season (1973). Oddly, he is not in the NFL Hall of Fame, despite being one of the most dominant defensive players of his era and having one of the cooler nicknames the sport has ever known (Hogmeat).[x]

Prior to Super Bowl V, Howley also was on the losing end of one of the most famous games in NFL history: The Ice Bowl. In sub-zero temperatures in Green Bay, Wisconsin, the Cowboys lost in the final seconds to the hometown Packers in the 1967 NFL Championship Game. On Green Bay’s winning TD, Howley (wearing his signature No. 54 jersey) just missed tackling Packers quarterback Bart Starr before he crossed the goal line.[xi]

The Cowboys’ playoff struggles from 1966-1970 are well documented, as Dallas became the proverbial “Wait ‘til next year!” team in the sport. At the end of both the 1966 and 1967 seasons, the Cowboys lost to the Packers, who went on to win the first two Super Bowls. In Both 1968 and 1969, Dallas lost to Cleveland in the NFL playoffs. In 1970, the Cowboys finally reached the Super Bowl, only to lose it at the end despite Howley’s heroic efforts.

He had an “uncanny instinct” on defense, often ignoring his assignment and “sniffing out the ball”, and that is how he ended up as this unique footnote in Super Bowl history. Howley told author Peter Golenbock in 2005, “In the early years all the Dallas fans wanted was a winner. Maybe that is human nature. Fans want to support a winner, not a loser ... it took us 11 years to do it.”[xii]

Perseverance defined Howley and his team: The Cowboys finally ascended to the top of the NFL pyramid in 1971, beating the Miami Dolphins, 24-3, in Super Bowl VI. The mere three points scored against Howley and the Dallas defense in that game remain a Super Bowl record for defensive effort—another testament to the spirit of Howley that just would not be conquered, even after multiple defeats over several years.

Howley was a big part of that Cowboys’ championship victory, recovering another fumble and intercepting another pass. Overall, he was a six-time Pro Bowl selection and is a member of the Dallas franchise’s Ring of Honor. Howley still lives in Dallas and works in the horse-breeding industry.

Yet there are no books written about him. Howley has been relegated to the margin in the history of the Super Bowl.

Howley was both the first member of a losing team to win the Super Bowl MVP and the first defensive player to win the award. Over time, most Super Bowl MVPs (41, to be exact) have been offensive “skill position” players (quarterbacks, running backs or wide receivers), but 11 defensive or special-teams players have won the award—including two of the last four winners, as the voters have come to appreciate winning contributions from hitherto underappreciated players.

Therefore, Howley started a legitimate shift in Super Bowl history, even if he still stands alone in that other prominent way. Along with New York Yankees second baseman Bobby Richardson (1960) and Los Angeles Lakers guard Jerry West (1969)—postseason MVP winners from the losing team in the World Series and the NBA Finals, respectively—Howley remains a historical anomaly in North American professional sports, and one Super Bowl viewers should appreciate and understand as they watch the Big Game and its commercials on February 4.

Howley himself finds the notoriety flattering. Over a decade ago, he said, “I get a lot of fan mail as a result of that ... I had a card here last year from a boy over in China. It’s kinda humbling when somebody that far away can still want your autograph.”[xiii] That does not sound like the mindset of a man his Dallas teammates nicknamed, “Hogmeat”, however: Howley may have been an exceptional player in a different era of football, when players had to get offseason jobs to augment their playing salaries. They were tough as nails on the field, but they were humble off of it.

We can watch the video clips on YouTube, and the game we see there is familiar—but Howley and Super Bowl V are from a different era of American football, and as a result, we may never see another Super Bowl MVP from the losing team again. After all, the Internet would explode, no doubt, since the fans themselves make up 20 percent of the voting totals these days for the award, and we know modern-day sports fans like winners—just like those Dallas Cowboys fans in the Hogmeat era.

Writer’s note: Five hockey players have won the Conn Smythe Award as the Stanley Cup Playoff MVP despite not being on the championship team, most recently in 2003. However, hockey is a different beast altogether, and that is a different story for a different blog post. Stay tuned, for when the Stanley Cup Finals take place in June!

About the author: Sam Fleischer a first-year Ph.D. student working under Dr. Matthew Sutton. His primary research is the cultural, economic and social influence of twentieth-century American sports on the United States. He earned a B.A. in English and History from the University of California and M.A. degrees in Education (Michigan State), English (Michigan State) and History (Arizona State).

Notes

i “Super Bowl V Box Score,” NFL.com, accessed December 27, 2017. http://www.nfl.com/superbowl/history/boxscore/sbv.

ii Hobbes LeGault, “A statistical analysis of the traditions of the Super Bowl MVP award,” University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2011.

iii John Mackey Award, John Mackey Super Bowl V Touchdown, YouTube video, 0:14, August 12, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xrg6rhKq27w; Tex Maule, “Eleven Big Mistakes,” Sports Illustrated, January 25, 1971.

iv “Super Bowl Records,” NFL.com, accessed December 27, 2017. http://www.nfl.com/superbowl/records/superbowls; “Super Bowl XV Box Score,” NFL.com, accessed December 27, 2017. http://www.nfl.com/superbowl/history/boxscore/sbxv.

v "Super Bowl V Recap: Colts vs. Cowboys," YouTube video, 3:22. January 11, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5aNW8xp2y0g.

vi Norm Miller, “Colts Save Kick for Final 5 Seconds: O’Brien FG nips Dallas, 16-13,” Daily News (New York), January 18, 1971.

vii Ibid.; John Steadman, “At Bottom of 22-Year Pile, Ex-Cowboy Still Insists He, Not Colts, Had Fumble,” Baltimore Sun, February 3, 1993.

viii “Chuck Howley,” Pro Football Reference, accessed December 27, 2017. https://www.pro-football-reference.com/players/H/HowlCh00.htm.

ix Peter Golenbock, Landry’s Boys: An Oral History of a Team and an Era (Triumph Books, 2005).

x Ibid.

xi "Cowboys vs. Packers: The Ice Bowl," YouTube video, 2:06, January 9, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oe0XChUkWgU.

xii Golenbock, Landry's Boys.

xiii Brian Jensen, Where Have All Our Cowboys Gone? (Taylor Trade Publishing, 2005), 22.

Inevitably, Chuck Howley’s name will come up during NBC’s telecast of the game, as it always does. As the big game approaches its end in the late hours of Super Bowl Sunday, modernity once again will test his relevance by asking the random trivia question: Who is Chuck Howley?

He is the only member of the losing team to win the Super Bowl’s Most Valuable Player Award.

|

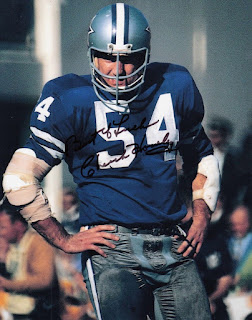

| Chuck Howley |

It happened on January 17, 1971, as Super Bowl V ended with the then-Baltimore Colts defeating the Dallas Cowboys, 16-13, on a last-second field goal by placekicker Jim O’Brien. But this game was far from “super” as the two teams combined for six interceptions and five fumbles—not to mention 14 penalties, ten on Dallas alone.[i] Baltimore won the game, despite turning the ball over seven times.

As the Colts had no worthy candidates for the game’s MVP Award and the Dallas defense forced those seven turnovers, Howley—playing linebacker and registering two interceptions and a fumble recovery—became part of Super Bowl lore. No other player in Super Bowl V stood as tall as Howley, even in defeat, and this is the only time, still, in Super Bowl history that a player who lost the game won the MVP Award.

Here is how it happened to the man his teammates called “Hogmeat.”

When the winning team stinks

Modern statistical analysis has changed the way we view sports accomplishments of the past, just as any historical framework has done previously. As one modern statistical analysis phrased the challenge, “Defensive MVPs are much less statistically straightforward and must therefore be analyzed on a case-by-case basis.”[ii] The problem with mere statistical interpretation of past accomplishments is the lack of context, but that’s why sports historians exist. We can start with the numbers, but qualitative analysis is just as valuable.

Context is simple here: Super Bowl V was a slop fest of bad football. No player on the winning team played consistently well enough to earn the award, although one could argue retrospectively for Baltimore tight end John Mackey: His second-quarter touchdown reception set a then-record for the longest scoring play in Super Bowl history, and it was the only play that kept the Colts in the game, as they trailed 13-6 at halftime (naturally, O’Brien missed the point-after kick).

However, Mackey’s play was the result of simply being in the right place at the right time on a twice-tipped pass that was not thrown his way.[iii] Plus, he only caught one other pass in the game, an insignificant five-yard reception. As for O’Brien, missing the extra point negated the heroics of hitting the game-winning field goal, and the numerous interceptions and fumbles by the Colts offense meant no other offensive player was going to be considered for the MVP.

Defensively, Chuck Howley accounted for three turnovers in the game. The only other player in Super Bowl history to achieve this was Oakland Raiders linebacker Rod Martin in Super Bowl XV when he intercepted Philadelphia Eagles quarterback Ron Jaworksi three times.[iv] Martin was not named the MVP in Oakland’s 27-10 victory, however, as the Raiders had offensive stars that day. The other nine defensive players since Howley to win the Super Bowl MVP award did not have a hand in three turnovers—although certainly they were a part of dominant defensive efforts that directly impacted the outcome of the game to the point they overshadowed the offensive contributors on their own team.

To address the contextual challenge above, the MVP voters at the time—sportswriters—watched a game that statistical analysis still can quantify today. The fact Dallas was leading the game midway through the fourth quarter meant that with a little less than eight minutes remaining, the Cowboys were in the dominant position to win.

This certainly influenced the thinking of the voters, despite the late comeback and eventual victory by the unimpressive Colts. Both Baltimore scores in the fourth quarter were set up by tipped-pass interceptions,[v] meaning all three Colts scores—including Mackey’s aforementioned touchdown catch—were somewhat “lucky” in the sense that the ball “bounced” Baltimore’s way at the most opportune times.[vi]

The Cowboys lost this game more than the Colts won it. All three interceptions thrown by Dallas quarterback Craig Morton came in the fourth quarter. The Baltimore defense itself did not produce a single performance like Howley’s in its efforts in stifling the Cowboys offense late, either. Three different players intercepted Morton, and the one Colts fumble recovery—a historically noted bad call that never should have happened—[vii] was not the result of anyone’s stellar individual effort. Howley was an obvious choice, statistically speaking—and in context of game flow and (surprising) end result.

Who is Chuck Howley?

Chuck Howley turns 82 years old in June 2018. He was born in West Virginia, attended West Virginia University and was drafted in the first round of the 1958 NFL Draft by the Chicago Bears.[viii] He was traded to the Dallas Cowboys in 1961 and played 13 seasons for America’s Team.

In examining the historical record of Howley’s sporting life, though, one key theme stands out: perseverance. Athletics came easy to Howley, as he lettered in five sports at WVU: football, gymnastics, swimming, track and wrestling.[ix] But when he got to the NFL, Howley struggled in his second season, thanks to a knee injury that almost ended his career.

He took the entire 1960 season off and then made his comeback with the Cowboys. The rest, as they say, is history. Another knee injury, late in the 1972 season, ended his career, as Howley played in just one game in his final season (1973). Oddly, he is not in the NFL Hall of Fame, despite being one of the most dominant defensive players of his era and having one of the cooler nicknames the sport has ever known (Hogmeat).[x]

Prior to Super Bowl V, Howley also was on the losing end of one of the most famous games in NFL history: The Ice Bowl. In sub-zero temperatures in Green Bay, Wisconsin, the Cowboys lost in the final seconds to the hometown Packers in the 1967 NFL Championship Game. On Green Bay’s winning TD, Howley (wearing his signature No. 54 jersey) just missed tackling Packers quarterback Bart Starr before he crossed the goal line.[xi]

The Cowboys’ playoff struggles from 1966-1970 are well documented, as Dallas became the proverbial “Wait ‘til next year!” team in the sport. At the end of both the 1966 and 1967 seasons, the Cowboys lost to the Packers, who went on to win the first two Super Bowls. In Both 1968 and 1969, Dallas lost to Cleveland in the NFL playoffs. In 1970, the Cowboys finally reached the Super Bowl, only to lose it at the end despite Howley’s heroic efforts.

He had an “uncanny instinct” on defense, often ignoring his assignment and “sniffing out the ball”, and that is how he ended up as this unique footnote in Super Bowl history. Howley told author Peter Golenbock in 2005, “In the early years all the Dallas fans wanted was a winner. Maybe that is human nature. Fans want to support a winner, not a loser ... it took us 11 years to do it.”[xii]

Perseverance defined Howley and his team: The Cowboys finally ascended to the top of the NFL pyramid in 1971, beating the Miami Dolphins, 24-3, in Super Bowl VI. The mere three points scored against Howley and the Dallas defense in that game remain a Super Bowl record for defensive effort—another testament to the spirit of Howley that just would not be conquered, even after multiple defeats over several years.

Howley was a big part of that Cowboys’ championship victory, recovering another fumble and intercepting another pass. Overall, he was a six-time Pro Bowl selection and is a member of the Dallas franchise’s Ring of Honor. Howley still lives in Dallas and works in the horse-breeding industry.

Yet there are no books written about him. Howley has been relegated to the margin in the history of the Super Bowl.

Hogmeat as history

Howley was both the first member of a losing team to win the Super Bowl MVP and the first defensive player to win the award. Over time, most Super Bowl MVPs (41, to be exact) have been offensive “skill position” players (quarterbacks, running backs or wide receivers), but 11 defensive or special-teams players have won the award—including two of the last four winners, as the voters have come to appreciate winning contributions from hitherto underappreciated players.

Therefore, Howley started a legitimate shift in Super Bowl history, even if he still stands alone in that other prominent way. Along with New York Yankees second baseman Bobby Richardson (1960) and Los Angeles Lakers guard Jerry West (1969)—postseason MVP winners from the losing team in the World Series and the NBA Finals, respectively—Howley remains a historical anomaly in North American professional sports, and one Super Bowl viewers should appreciate and understand as they watch the Big Game and its commercials on February 4.

Howley himself finds the notoriety flattering. Over a decade ago, he said, “I get a lot of fan mail as a result of that ... I had a card here last year from a boy over in China. It’s kinda humbling when somebody that far away can still want your autograph.”[xiii] That does not sound like the mindset of a man his Dallas teammates nicknamed, “Hogmeat”, however: Howley may have been an exceptional player in a different era of football, when players had to get offseason jobs to augment their playing salaries. They were tough as nails on the field, but they were humble off of it.

We can watch the video clips on YouTube, and the game we see there is familiar—but Howley and Super Bowl V are from a different era of American football, and as a result, we may never see another Super Bowl MVP from the losing team again. After all, the Internet would explode, no doubt, since the fans themselves make up 20 percent of the voting totals these days for the award, and we know modern-day sports fans like winners—just like those Dallas Cowboys fans in the Hogmeat era.

Writer’s note: Five hockey players have won the Conn Smythe Award as the Stanley Cup Playoff MVP despite not being on the championship team, most recently in 2003. However, hockey is a different beast altogether, and that is a different story for a different blog post. Stay tuned, for when the Stanley Cup Finals take place in June!

About the author: Sam Fleischer a first-year Ph.D. student working under Dr. Matthew Sutton. His primary research is the cultural, economic and social influence of twentieth-century American sports on the United States. He earned a B.A. in English and History from the University of California and M.A. degrees in Education (Michigan State), English (Michigan State) and History (Arizona State).

Notes

i “Super Bowl V Box Score,” NFL.com, accessed December 27, 2017. http://www.nfl.com/superbowl/history/boxscore/sbv.

ii Hobbes LeGault, “A statistical analysis of the traditions of the Super Bowl MVP award,” University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2011.

iii John Mackey Award, John Mackey Super Bowl V Touchdown, YouTube video, 0:14, August 12, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xrg6rhKq27w; Tex Maule, “Eleven Big Mistakes,” Sports Illustrated, January 25, 1971.

iv “Super Bowl Records,” NFL.com, accessed December 27, 2017. http://www.nfl.com/superbowl/records/superbowls; “Super Bowl XV Box Score,” NFL.com, accessed December 27, 2017. http://www.nfl.com/superbowl/history/boxscore/sbxv.

v "Super Bowl V Recap: Colts vs. Cowboys," YouTube video, 3:22. January 11, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5aNW8xp2y0g.

vi Norm Miller, “Colts Save Kick for Final 5 Seconds: O’Brien FG nips Dallas, 16-13,” Daily News (New York), January 18, 1971.

vii Ibid.; John Steadman, “At Bottom of 22-Year Pile, Ex-Cowboy Still Insists He, Not Colts, Had Fumble,” Baltimore Sun, February 3, 1993.

viii “Chuck Howley,” Pro Football Reference, accessed December 27, 2017. https://www.pro-football-reference.com/players/H/HowlCh00.htm.

ix Peter Golenbock, Landry’s Boys: An Oral History of a Team and an Era (Triumph Books, 2005).

x Ibid.

xi "Cowboys vs. Packers: The Ice Bowl," YouTube video, 2:06, January 9, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oe0XChUkWgU.

xii Golenbock, Landry's Boys.

xiii Brian Jensen, Where Have All Our Cowboys Gone? (Taylor Trade Publishing, 2005), 22.

super bowl live streaming 2020

ReplyDelete