"A Beginning for Other Women": The Marital Rape Exemption and the Rideout Case

On March 17, 2017, an Oregon man named John Rideout received a sentence of more than sixteen years in prison for rape and sodomy. His two victims, a woman he knew from church and his ex-girlfriend, spoke before a judge at the Marion County courthouse before sentencing; one said she hoped Rideout received help, while the other declared, “I am a victim no longer.”[1] Addressing the court, Rideout maintained his innocence, and then stated he was proud of his accusers, because they “stood up to me.”[2]

Nearly forty years earlier, another woman stood up to Rideout: his former wife, Greta. On October 10, 1978, Greta Rideout, then 23 years old, telephoned the Women’s Crisis Center in Salem, as well as the Salem Police Department, alleging that her 21-year-old husband beat and raped her. She underwent a medical examination at Salem Memorial Hospital, where the doctor who examined her later testified she suffered from bruising around the left eye and cheek; her lips appeared bitten; and she had “probably” been forced into an “episode of intercourse.”[3] Questioned by the Salem police on October 13, 1978, John Rideout was charged with first-degree rape five days later and became the first husband in the United States charged with raping his wife.[4]

source: Gannett

Before the 1970s, the idea that a husband could rape his wife would have been considered an oxymoron in American culture. Greta Rideout’s case marked a beginning in the effort to change the American legal system’s embrace of English common law that defined women’s bodily autonomy as subordinate to the will of a husband. English settlers arriving in Jamestown at the beginning of the seventeenth century believed that the differences between men and women were part of a “divinely sanctioned plan” and essential to the establishment of a peaceful social order.[5] Women’s subordination to men became central to the establishment of patriarchal households in the American colonies—supported by the law, the church, and the state. Essential to the patriarch’s power within his household was unlimited sexual access to his wife. From the eighteenth century up until the late 1970s, legal tradition and social norms supported the marital rape exemption despite the advancement of women’s rights in other realms of everyday life.

The marital rape exemption originated with eighteenth century legal scholars who developed rules for the marriage contract reflecting the belief that a husband and wife were partnered in a private economic relationship.[6] Under coverture, a wife became one with her husband and forfeited her legal existence, effectively eliminating her rights under the law while he assumed authority over her.[7] Sir Matthew Hale, the most well-known British jurist to influence common law relative to the marital rape exemption, declared, “… the husband cannot be guilty of a rape committed by himself upon his lawful wife, for by their mutual matrimonial consent and contract the wife hath given herself unto her husband, which she cannot retract.”[8] According to historian Sharon Block, attempting to trace coerced sex within marriage in early America is nearly impossible because such acts were “neither a legal nor a conceptual possibility.”[9] In keeping with Hale’s interpretation of common law, all sexual relations within marriage were considered automatically consensual, and a woman’s sexual choices were one and the same with her husband’s sexual demands.

In her book, Rape and Sexual Power in Early America, Block presented a 1793 case in Pennsylvania where a wife accused her husband of committing sodomy against her. For such a charge, evidence of force was not required as all acts of sodomy were considered criminal acts whether consent was given or not. A grand jury refused to indict the accused husband, however, and Block suggests early Americans did not know how to handle a wife’s accusation of sexual misconduct against her husband.[10] In an 1857 case in Massachusetts, Commonwealth v. Fogerty, the court held a husband could not be convicted of raping his wife; this was the first known case in the United States to adopt Hale’s statement as law.[11]

source: Wikipedia Commons

Courts continued to provide cover against any scrutiny of the privileges granted to men within marriage due to the institution’s sanctified status, with the sexual foundation of the marriage contract providing husbands their unquestioned conjugal rights. This also extended to protection for husbands who abused their wives in any capacity, such as an 1874 battery case in North Carolina that determined the following: “If no permanent injury has been inflicted, nor malice, cruelty nor dangerous violence shown by the husband, it is better to draw the curtain, shut out the public gaze, and leave the parties to forgive and forget.”[12] While few such battery cases ever made it to court, there is no evidence that any marital rape cases were tried before the Rideout case in 1978.

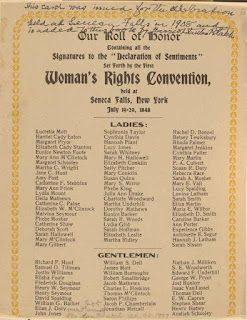

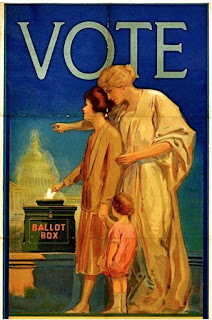

As women began to gain individual rights under the law in the nineteenth century, the one part of the marital contract that remained steadfast was the legal interpretation that a husband’s rights included sexual ownership of his wife. As Rebecca M. Ryan noted, overturning the marital rape exemption broke the foundation of a husband’s patriarchal identity.[13] While much credit is given to the battered women’s movement of the 1970s for shifting public perception about women’s bodily autonomy and initiating legislation that made marital rape a crime, their success had its origins in the nineteenth century. Following the first women’s rights convention at Seneca Falls in 1848, American feminists led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott launched the woman suffrage movement, making the first public demand for women’s voting rights. In addition to seeking a political voice for women, these activists also sought to challenge the legal traditions vested in natural and common law subjugating women to the will of their husbands.

source: Wikipedia Commons

Nineteenth-century feminists often identified a woman’s right to control the terms of marital intercourse as a foundation of women’s equality, without which “full property rights and even suffrage would be meaningless.”[14] Ultimately, the only changes activists were able to achieve in the nineteenth century were modest reforms related to divorce law. Marriage was thought to exist above the individual; thus, the institution enjoyed privileges that “placed it literally above the law.”[15]

Following the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment on August 18, 1920, giving women the right to vote in the United States, social movements for women’s rights became much less visible. It was not until the early 1970s that the battered women’s movement began to raise the issue of interpersonal violence (IPV) as a public health concern throughout the country. In addition to addressing physical violence, activists also began to address the issue of marital rape. However, they found it difficult to implement change within law enforcement agencies and the court system because police officers and judges often resisted such changes. In addition, while most people supported the work being undertaken by battered women’s movement activists, politicians failed to approve funding measures to support their efforts.

source: Wikipedia Commons

One of the main areas for legislative action identified by battered women’s activists centered on the response of law enforcement officers to domestic disturbance calls. Political pressure brought by women’s groups resulted in a nationwide movement toward arrest being the preferred response to IPV.[16] The 1977 Abuse Prevention Act put Oregon on the map as the first state to require police to make arrests in suspected IPV cases. In addition, the law removed the marital exemption in rape cases so husbands could be charged with a crime, becoming one of only three states at the time to have laws revoking spousal immunity.[17] According to witness testimony, Greta Rideout knew about the new law and allegedly threatened her husband with reporting him to authorities.[18]

Ahead of John Rideout’s trial in December 1978, newspaper articles stressed the importance of the case given its notoriety as the first instance of marital rape to be brought to trial. Marion County District Attorney Gary Gortmaker noted at the time there was considerable national interest in the Rideout case: Greta would be at a disadvantage during the trial because she would be tried first, then the law, and finally, the defendant.[19] Gortmaker described Greta as an “attractive woman,” and he warned her that she would be subjected to intrusive questions about not only the alleged rape but “everything she’s ever done of a sexual nature in the past year.”[20] John Rideout’s defense attorney, Charles Burt, stated his client sincerely believed “if you are married to a woman, you have a right to sex.”[21]

During the trial, Burt portrayed Greta as a troubled woman with “a severe sexual problem” that she’s had for “a long time.”[22] In his opening statement, Burt noted Greta used the incident to achieve self-gratification by casting herself in the limelight, even going so far as to tell several witnesses she had received an offer from Warner Bros. to make a movie about her case. In addition, Burt brought up she had told a neighbor that she had undergone two abortions.[23] The defense also discussed a prior rape accusation Greta made against John Rideout’s stepbrother. She did not report that incident to the police, allegedly recanting the story to her husband.[24]

During the trial, John Rideout’s defense team asked Judge Richard D. Barber to acquit their client on the grounds that marital privilege was still a defense for rape, while Oregon’s rape laws were unconstitutional and violated a couple’s right to privacy.[25] However, Judge Barber refused to do so. In his testimony, the defendant stated he had slapped his wife across the face but stopped because he was “really agitated.”[26] He insisted he had never hit his wife intentionally before; he then had apologized, and he claimed the couple had consensual intercourse following the incident. In her testimony, Greta stated John repeatedly hit her in the face with their two-year-old daughter present, forced her to the ground, and put his hands around her throat, “forcing her to submit.”[27] On December 27, 1978, the jury of eight women and four men found John Rideout not guilty in the rape of his wife.

source: Flickr

One juror, Jean Kay Lent, the wife of an Oregon Supreme Court Justice, stated the jury was not convinced beyond a reasonable doubt of Rideout’s guilt. Another juror, Pauline Speerstra, stated she would “like to see another case brought. I don’t think this case decides anything.”[28] The verdict disappointed women’s rights activists. Norma Joyce of the Salem Women’s Crisis Center, the same facility Greta Rideout turned to in the aftermath of her alleged rape, described feeling shocked by the jury’s decision. She worried women would hesitate before seeking justice through the legal system, as they were very aware of how “traumatizing” it is to go through a rape trial.[29] However, Greta Rideout, while disappointed and angered by the outcome, said if given the chance she would make the same decision again. She stated, “I saw it as a selfish act for myself at first, but now I see it as a beginning for other women.”[30]

Today marital rape is criminalized in all fifty states, but loopholes remain due to the difficulty in completely overturning all traces of the English common law forming the foundation of American legal traditions. Since the Rideout case, states have attempted to remove or modify exemptions that remain but met with little success. However, the #MeToo era renewed interest and politicians have taken notice at the state level. In May 2019, the Minnesota state legislature voted to eliminate exemptions preventing prosecution for husbands who raped their wives while they were drugged, unconscious, or otherwise incapacitated.[31] Seventeen states still retain such loopholes regarding incapacitation, including Washington and Idaho. Other states have loopholes related to age, relationship, use of force, or the nature of the penetration. In addition, some states allow for only a short timeframe for victims to report spousal rape.[32]

Greta Rideout’s case marked a beginning in the effort to change the American legal system’s embrace of English common law that held women’s bodily autonomy as subordinate to the will of a husband. This October, Domestic Violence Awareness Month is observed as it has been since 1981, and advocates across the nation encourage people to remember there are still countless victims and survivors, their children and families, and communities impacted by interpersonal violence: There is still much work to be done.

About the author: Samantha Edgerton is a first-year doctoral student working with Dr. Laurie Mercier. Her primary research fields are women and gender, race and ethnicity, social movements, and popular culture in the twentieth-century United States. Her Master’s thesis, “Better Than Being on the Streets”: Oregon, Idaho, and the Battered Women’s Movement, centered on interpersonal violence (IPV) and the battered women’s shelter movement in Oregon and Idaho from 1975-1994.

[1] Andrew Selsky, “Oregon man accused of raping his wife in 1978 gets 16 years in other sex assaults,” The Seattle Times, March 18, 2017, https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/oregon-man-accused-of-raping-his-wife-in-1978-gets-16-years-in-other-sex-assaults/ (Accessed October 9, 2019).

[2] Ibid.

[3] Cynthia Gorney, “The Rideouts: Case Closed, Issue Open,” The Washington Post, December 29, 1978, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1978/12/29/the-rideouts-case-closed-issue-open/c53271f7-3e26-4721-8b05-2d8f4d569212/ (Accessed October 13, 2019).

[4] Ibid.

[5] Kathleen Brown, Good Wives, Nasty Wenches, and Anxious Patriarchs: Gender, Race, and Power in Colonial Virginia (University of North Carolina Press, 1996), 1.

[6] William Blackstone, Blackstone’s Commentaries, ed. George Sharswood, 325 (Philadelphia: Lippincott Co., 1896).

[7] Rebecca M. Ryan, “The Sex Right: A Legal History of the Marital Rape Exemption,” Law & Social Inquiry 20, no. 4 (1995): 998.

[8] Sir Matthew Hale, The History of the Pleas of the Crown 629 (Emlin ed. 1736).

[9] Sharon Block, Rape and Sexual Power in Early America (University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 78.

[10] Ibid., 79.

[11] Lalenya Weintraub Siegel, “The Marital Rape Exemption: Evolution to Extinction,” Cleveland State Law Review 43, No. 351 (1995), 3.

[12] Rollin M. Perkins, Cases and Materials on Criminal Law 662, 2nd edition (Brooklyn, NY: Foundation Press, 1959); State v. Oliver, 70 N.C. 60 (1874).

[13] Ryan, “The Sex Right,” 947-948.

[14] Jill Elaine Hasday, “Contest and Consent: A Legal History of Marital Rape,” Calif. L. Rev. 88 (2000): 1385.

[15] Ryan, “The Sex Right,” 946.

[16] David Hirschel, Eva Buzawa, April Pattavina, and Don Faggiani, “Domestic Violence and Mandatory Arrest Laws: To What Extend Do They Influence Police Arrest Decisions,” Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Vol. 98, Issue 1 (Fall, 2008), 257-258.

[17] “Husband is charged with raping wife,” The Seattle Times, December 17, 1978.

[18] Gorney, “The Rideouts: Case Closed, Issue Open.”

[19] “Husband is charged with raping wife,” The Seattle Times, December 17, 1978.

[20] Ibid.

[21] United Press International and Associated Press, “Lawyer portrays ‘sexual problems’ in Ore. rape case,” The Seattle Times, December 21, 1978.

[22] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] “Judge refuses to acquit man charged with raping his wife,” The Seattle Times, December 27, 1978.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid.

[28] “Rape trial: Husband not guilty of charge brought by wife,” The Seattle Times, December 28, 1978.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Julie Carr Smyth and Steve Karnowski, “Some states seek to close loopholes in marital rape laws,” apnews.com, May 4, 2019, https://apnews.com/3a11fee6d0e449ce81f6c8a50601c687 (Accessed October 20, 2019).

[32] Ibid.

Thanks for sharing very nice detailed information. Please check haute her tips for face

ReplyDelete