“Undesirable Citizens and Neighbors”: Japanese Immigration and Life in the Pacific Northwest, 1890-1924

On March 16, 2021, a shooting spree took place in Atlanta, Georgia and resulted in eight victims killed and one injured. The shooting, which occurred at three different massage parlors and spas, has prompted a deeper national discussion than one typically had after such a tragedy. With the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, anti-Asian hate crimes have exploded since the outbreak of the virus as many Asian-Americans have been blamed for the spread of the virus. As the Atlanta shooting has highlighted the surge of anti-Asian sentiments across the country, the United States once again reckons with its ugly history of racism against Asians. Though many different groups of Asian-Americans have experienced discrimination in their history in the United States, the experience of Japanese Americans is well-known and pertinent to the discourse. Despite being seen as a “model minority” in the years since World War II, early Japanese immigration is riddled with examples of discrimination and violence in areas where significant populations of Japanese lived, such as Idaho, Oregon, and Washington. While countless Japanese immigrants experienced hostility, recounting their struggles without detailing their successes in the United States only tells part of the story as tens of thousands managed to settle down in this new land. What can the experiences of first-generation Japanese immigrants reveal about anti-Asian sentiments and life in the Pacific Northwest? Despite facing consistent pressure from nativists and discriminatory legislation, Japanese immigrants were motivated and able to carve out spaces within the Pacific Northwest. With the help of community networks and religious organizations, this first generation of Japanese found a home in a land that could hostile. Braving discrimination and rigorous working conditions, Japanese men and women alike laid down a foundation for future Japanese Americans to become an integral part of American society.

|

| Fig. 1: Japanese American families in Hood River, Oregon, 1915. Densho Digital Repository |

Coming to America

The historical study of Japanese immigration

is usually sectioned off by specific eras and periods. While the amount of Japanese migrants coming to the United States was negligible until the late 19th century, events

and movements in the US and Asia were already shaping their futures in America. With the passage

of the infamous 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, nativists and anti-Asian

organizations alike had scored a decisive blow against a perceived Asian menace

but had inadvertently created opportunities for other non-Chinese immigrant groups. With

Japanese laborers finding scant opportunities for work in a rapidly

industrializing Japan and with American industries needing large quantities of cheap labor, a pipeline for

immigration quickly developed. With the first wave of Japanese immigration

in the 1890’s, many found ample employment in areas such as

agriculture, logging, mining, and railroads.[1] The lack of available work in Japan was a key factor in the drive for immigration

as incomes remained low while the cost of living surged. When considering his options, one Japanese man recalled, “I prayed to God, asking what I should do.

Then I heard a voice saying, ‘Go to America.’” As Japanese migrants found

success in this new land, their accounts tantalized friends and family back

home. Letters sent back to Japan raved of the possibilities in the United

States, as some told of money growing on trees.[2] Another important motivating factor for many Japanese to immigrate to America were

guidebooks. Pamphlets like Guidance for Going to America, The New Way

to Go to America, and Up-to-date Policy for Going to America were

cheap and extremely popular for many young men, as one particular pamphlet was

reported to have sold two thousand copies each week.[3]

Driven by publications at home and the chance to make a living, the Japanese

began to arrive in greater numbers around the turn of the century to a land

with opportunity and hazards.

| Fig. 2: Issei Workers at a Railroad Camp, circa 1895. Discover Nikkei |

Once committed to seeking out their fortunes overseas, the incoming Japanese began a long journey across the Pacific. Oftentimes carrying little more than a couple pieces of luggage, the trek to a port city like Seattle typically lasted at least two weeks. Upon arriving in the United States and passing health examinations, few had contacts and frequently depended on already established Japanese to ease them into their new country. Staying with Japanese-owned boarding houses, new immigrants found a temporary place to sleep and rest before finding work.[4] Though this first generation of Japanese, known as the Issei, discovered a great deal of opportunity in the western United States, the number of incoming Japanese to America paled in comparison to the millions of newly arriving European immigrants on the East Coast. Growing from a lowly 148 total in 1880, the census reported 2,049 Japanese in 1890 and a further 24,326 in 1900. As the Issei arrived on the West Coast, a significant portion settled in California as the state on average held more than half of the Japanese population in most census reports until 1940.[5] Nevertheless, the states that made up the Pacific Northwest also held significant populations of Issei as Washington and Oregon were home to many. By 1900, the populations of Japanese in Washington and Oregon reached 5,617 and 2,501, respectively, constituting about 44 percent of the total population on the west coast.[6] As more Issei arrived in the United States, their presence drew greater attention and scrutiny from their new countrymen.

Settling in a Foreign Land

While money was the main draw for

many Japanese immigrants, ideas on how long one planned on staying in the

United States differed greatly. Many Issei immigrated with the intention of

making a significant amount of money and then returning to Japan, now able to

pay off debts or a dowry for a wife. For a second son, America provided an

opportunity to make a substantial amount of money in a short amount of time. Many intended to live in America temporarily, with the goal of making $1000-$3000 dollars in

three to five years and returning home to a greater station in life. Despite some

achieving this goal and returning back to Japan, many Issei found the American

way of life more inviting. One Seattle Issei recalled, “I went to the States in

1917 and in five years I had achieved my goal, but I had meantime become so

used to American life that I decided not to return to my mother country. I only

returned once, to marry my wife, Aki, and then came back to America.” Though

staying in America seemed an easy decision, life as an immigrant was filled

with challenges. Many Issei worked in occupations with a great deal of manual labor

and little rest. White coworkers were oftentimes highly antagonistic to their

Japanese counterparts as they had little recourse for any abuses. As one Issei stated, “Even so

we couldn’t protest outwardly; if we did, we would be told to ‘Go home, Jap!’

and would be fired immediately.”[7] Even worse than strenuous work and harassment on the job was the organized

violence levied against Japanese workers. By 1900, incidents of violence

occurred in every state in the Pacific Northwest as white mobs began attacking

Japanese with the same vigor as they had the Chinese before them. In 1897, twenty

Japanese railroad workers were attacked near Lake Couer d’Alene, Idaho by white

workers who feared losing their jobs. In the next couple of years, mobs formed

in Portland, Oregon to threaten four Japanese workers and in Spokane,

Washington where thirty Japanese took flight in rail cars after a bloody brawl

with white railway workers.[8]

In spite of the difficulties and violence, the Issei maintained their foothold

in America and sought to put down roots.

|

| Fig. 3: Wedding Portrait of Kamematsu and Shizuko Norimatsu, circa 1916. Densho Digital Repository |

For the men who wanted to make the United States their home, they were presented with the difficult task of finding a Japanese wife to settle down with. Few Japanese women came to the United States alone, leaving Japanese men to looked to the “picture bride” method to find a wife. With the help of a nakado, or matchmaker, Issei men relied on pictures to pick out a prospective bride before having them sent to the United States. In Japanese society, arranged marriages were the standard as choosing a partner or even dating were socially unacceptable, making picture marriages an extension of a common practice. While some women had jobs of their own and little interest in marriage, pressures from the deeply patriarchal Japanese society won over even the most independently minded women. For schoolteacher Teiko Tomita, contact with her future husband was limited to a short exchange of letters before the wedding day as the couple eventually settled in Wapato, Washington. While the two were a happy match, many Issei women arrived in America only to find their husband older than depicted in their photograph or appearing totally different than expected. Despite picture marriage being acceptable in Japanese society, Americans were shocked at the practice and the idea of marrying before having seen their partner.[9] Though Americans focused in on eventually ending picture marriages, many Issei women arrived in the United States as picture brides. With the Issei now having families, they became more connected to America and more determined to make this country their new home.

At the dawn of the 20th century, Japan was on the ascendant on the world stage. After years of rapid modernization, Japan proved itself when it came out victorious in the Russo-Japanese War, shocking many European powers. Japan’s prowess was also noted in the United States, with Issei receiving praise for their motherland's success. Businesses eagerly hired Japanese and Americans respectfully referred to some Issei as ‘Togo’, the name of the famous Admiral who defeated the Russian naval fleet.[10] This respect carried over into the world of sports when the famous traveling Waseda Japanese baseball team arrived in Washington. Playing against formidable teams such as the University of Washington varsity squad and the semi-professional Seattle Rainiers, the Waseda club held its own as many of Seattle’s Japanese community showed their support for the team. The Waseda baseball team was not only admired by their countrymen but also white Americans as well, with two young boys eagerly served as equipment managers. After a victory against the Rainiers, team captain Shin Hasido happily recalled the moment of celebration. “When we won the game by 2 to 1, [the boys] jumped on me and called me ‘Good boy, good boy!’ with big smiles. In the meantime, many people came down from the stands and heartily praised out performance, shaking our hands. We were so delighted and would never forget that wonderful moment.”[11] Nevertheless, this brief moment of recognition soon descended into suspicion in the political stage while the Issei themselves began to experience concerted efforts to marginalize them.

Closing America's Open Door

These first attempts originated in

California, a stronghold of anti-Chinese sentiment once again boiled over with

ethnic tensions. In 1906, the San Francisco Board of Education moved to send

all Chinese, Korean, and Japanese children to a segregated “Oriental School,”

an action that sparked an enormous international reaction. Confident after its victory

over Russia, Japan stridently protested the insult and put pressure on the

United States government to act. Not wanting to incite a political incident

with Japan, President Theodore Roosevelt worked to reach a compromise with San

Francisco officials. While segregation was defeated, exclusionists and

nativists won a larger prize when Roosevelt negotiated the 1907 Gentlemen’s

Agreement with Japan. The agreement was the first decisive victory against

Japanese immigration as Japan agreed to only restrict the immigration of laborers into

the United States.[12]

Despite this massive blow to immigration, the door to America was not completely

shut. Japan agreed only allow passports to laborers returning to the US as well

as to their wives, children, and parents.[13]

While Californians won a major legislative battle against Japanese immigration,

the nativist crusade was far from over. Ending picture marriages, depriving

non-citizens of land ownership, and ending all immigration from Japan remained

as objectives yet to be fulfilled. Outside of California, Issei in the Pacific

Northwest also faced pressure from their increasingly hostile neighbors.

Fig. 4: Article from the Monroe-Monitor Transcript, April 21, 1911.

After the passing of the Gentlemen’s Agreement, the tide of public opinion soon began turning against the Issei. Though many Japanese had already experienced prejudice and even violence in the United States, the severity was consistantly growing. As it had been during the anti-Chinese movements in previous decades, labor, land, and Japanese businesses became the focal point for a great deal of agitation. In 1907, a Japanese-owned restaurant in the city of Bellingham in northern Washington was attacked by a mob that hurled insults and attempted to assault the bewildered targets.[14] In the rural town of Snohomish, Washington, local newspapers reacted strongly when Japanese farmers attempted rent additional ranches in the area. Labeled as “undesirable citizens and neighbors,” the papers went on to warn of further Japanese incursions if not immediately countered. Ominously, the article went on to say that “unless strong objection is put forth soon,” the Japanese invasion would continue.[15] Though many Japanese quietly suffered abuses by white Americans, not all incidents were met passively. In Palouse, Washington, restaurant owner Frank Uyeda was involved in an altercation with a lumberjack that had refused to pay for his meal. After the initial skirmish was broken up, Uyeda returned to his restaurant for a butcher knife and repeatedly slashed the recalcitrant lumberjack, severely injuring the man.[16] These incidents were few as white Americans still wielded considerable power over Japanese lives. The logging industry, at one time a major employer of Issei labor in Oregon and Washington, became another target for whites to drive out Japanese workers. The number of Japanese employed in logging began to decrease after the passage of the Gentlemen’s Agreement as government reports detail strong agitation. Japanese were not only refused employment, mill-town communities prevented Issei workers from stepping off trains into their towns. Alongside constant harassment, Issei were also paid less than white workers, sometimes earning a full dollar less than their white co-workers.[17] As the 1910’s continued, the situation for the Pacific Northwest Issei only grew more tenuous. Though maligned by society, the outbreak of World War I meant possibilities for some.

The First World War was a destabilizing event in the history of the world, but it was also an event that offered a chance to some. While Imperial Japan fought on the side of the Entente, some Japanese fought against the Central Powers under a different flag. Canada, home to a substantial population of Issei, was an early participant in the war. The exigencies of the war were an open door for Japanese in Canada to serve and possibly help to reduce the nativist attitudes at home. While only 196 Issei served in the Canadian armed forces, they more than proved themselves in combat. Taking part in bloody battles on the frontlines, one veteran recalled, “There are brave men among white soldiers, but they all duck hastily when the bullets fly as we are stretching barbed wire fencing. They were all surprised that Japanese could keep so cool.” Out of the small number of volunteers, 54 were killed and 93 others were injured as the Issei soldiers earned high honors with Distinguished Service Crosses, Victoria Crosses, and other awards. When the United States entered into war against the Central Powers, American Issei were also quick to serve. While specific numbers are unclear, over 500 Asians, including Japanese, Chinese, and Koreans, served with the United States during the war. As a reward for their service, some Issei veterans were able to use their war record to attain citizenship. Sadahiko Ikoma, a Seattle Issei, recalled that he was asked by a draft board member, “‘If America needs you, would you volunteer and go to the European front?’ I answered, ‘Yes.’ After the war, when I wanted to be naturalized, I found that the record of the conversation had been kept and it helped me to get American citizenship.”[18] For the few Issei American veterans, service was the key to attaining US citizenship, a privilege that the vast majority of Japanese immigrants were excluded from receiving. A generation later, their children would use their excellent war record during World War II to prove themselves in the face of fierce discrimination. While the Issei had sacrificed in combat, they did not receive a hero’s welcome. After the war, anti-Japanese sentiment was beginning to reach its climax.

World War I and the Rise of Exclusionism

In the United States, the years

following World War I were marked by tension and episodes of racial violence.

Mob violence, lynching, and the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in the South are

particularly notable in this period, but Issei in the Pacific Northwest experienced

a reinvigorated anti-Japanese movement in their homes. White soldiers returning

home experienced difficulty finding jobs and Japanese were easy targets for

blame. Jealous and threatened by the economic success of the Issei, the

anti-Japanese movement was rekindled and was directed towards enacting long

desired exclusionary legislation. Powerful organizations like the Anti-Japanese League

and the American Legion coordinated together for this goal and also mobilized other

nativist groups along the west coast.[19]

Serving alongside these powerful groups was another influential actor, the

newspaper. Certain newspapers were some of the most vituperative and vocal

critics of the Japanese, promoting the “Yellow Peril” narrative with

sensational headlines that demonized the Issei. In Hood River, Oregon,

local newspapers featured several negative articles on Japanese farmers as racial

tensions mounted. Stories depicted the Japanese as living in squalor while

working longer hours than their white counterparts. The newspapers also singled

out Japanese women and children as farmers criticized the Japanese for having

pregnant women and young children working in the fields.[20]

Though local newspapers sparked a great deal of anti-Japanese sentiment, major

newspapers were also strong outlets for such sentiments. One of the most

aggressively nativist and sensationalist newspapers was the Seattle Star,

a publication that focused a great deal of attention on the Japanese. Headlines

on the Star discussion the “Japanese problem” were extraordinary and

attention-grabbing with articles titled “Japs Grab 600,000 Acres in

California,” “Jap Trickery Exposed,” or were capitalized with examples such as “JAPS’

PLANS MENACE WHITE CIVILIZATION” and “WILL YOU HELP TO KEEP THIS A WHITE MAN’S

COUNTRY?”[21] While

many powerful interests came together for a massive push for exclusion, some

groups came to the defense of the Japanese.

|

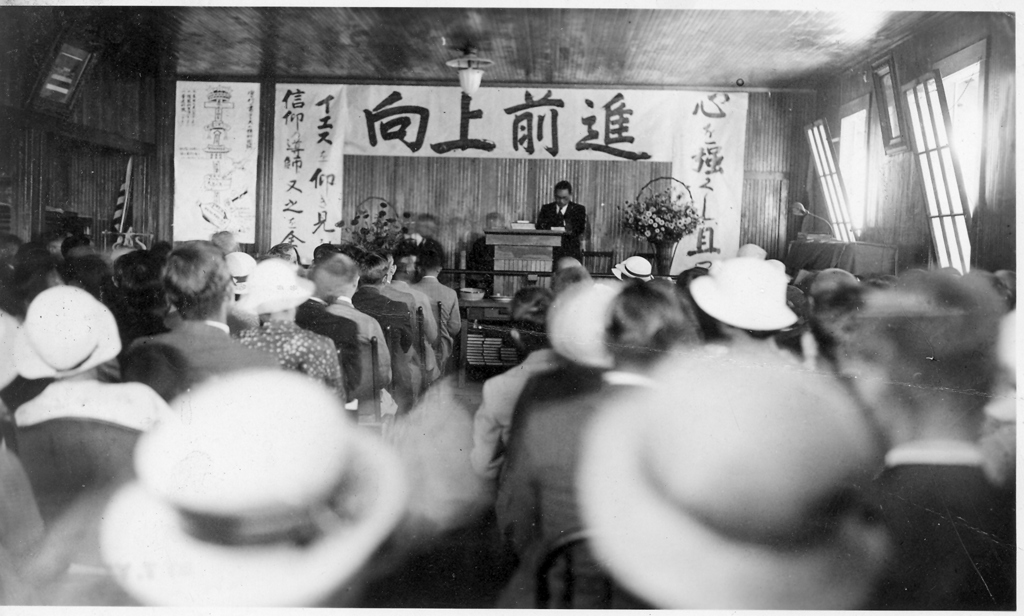

| Fig. 5: Reverend Wada speaking at a Japanese church, date and location unknown. Densho Digital Repository |

Despite not being typically thought of as a force for social or racial justice, American churches were oftentimes some of the only institutions that defended the Japanese. Though this relationship came to the forefront during World War II, churches stepped up to help counter anti-Japanese sentiments during the push for exclusion. As the Issei began arriving on the west coast, the church was one of the few institutions that pursued and assisted migrants in adjusting to life in America. As the Japanese interacted with Christianity, they found similarities with Buddhist views on ethics. Weary and homesick Issei also found comfort in the social welfare characteristics espoused by churches. In terms of specific denominations, the Methodist church was particularly focused on its outreach programs to the Japanese and was rewarded by its efforts. At the Japanese Methodist church in Portland, Issei enjoyed social activities, found a place to stay, and received assistance with finding a job within the church or elsewhere.[22] While churches could provide valuable emotional, financial, and spiritual support, some churches did not shy away from vocally challenging nativist rhetoric. A pamphlet distributed by the Seattle-based Pacific Northwest Japanese Christian Federation showed the religious roots behind their defense of the Issei. “We have but one way to solve [racial prejudice] and this is through the great teachings of Jesus Christ: the great ideal, ‘the equality of men,’ and ‘they are all brothers who live in the four quarters of the world.” When discussing the motives for anti-Japanese sentiment, the pamphlet astutely blamed “the prank of yellow journalism, the campaign of lies of cheap politicians, and race prejudice.”[23] The outsized influence of California’s virulent campaign against the Japanese was a particularly noticeable phenomenon that was also addressed by some activists. During an address hosted at the First Congregational Church in Boise, Idaho, speaker Colonel John Powell Irish pointed out the trend taking root in Idaho. When speaking about the situation, Irish declared that the blame laid with “the literature finished by the venal press and the statements made by the venal mouths of the anti-Japanese agitators in [California].”[24] While nativist alliances and interests proved to be too powerful for churches to counter, their help to the Japanese community cannot be discounted. Churches assisted thousands of Issei during a time when such actions were incredibly unpopular, giving many a chance to adjust and survive within the United States.

Issei Women and the Triumph of Exclusion

For many Japanese immigrants, life

in America was as harsh as it was different from their homeland. Though the

United States presented great opportunities and freedoms, life in America demanded

constant labor all while dealing with prejudice. This especially becomes true

in the case of Issei women as they were not only mothers and wives, but

pioneers in a strange land. Many Issei women came to the United States with

similar optimism to their husbands had and were similarly disillusioned when

faced with reality. Issei women were shocked by the harshness of life in the

Pacific Northwest, as many assisted their husbands in endless agricultural

labor along with constant chores at home. Living conditions were also

oftentimes very poor as many Issei could only afford to live in small homes

that lacked basic amenities such as electricity, running water, or basic

plumbing. When thinking back to the quaint town she expected live in, one Hood River women recalled, “This was not what I had expected! I

wondered why I had come!... I had left a large home in Japan for a small, dark,

two-room cabin! I thought, ‘Did I leave Japan to come to a place like this?’ It

was much worse than I could possibly have imagined!”[25]

On top of the rough nature of American living, Issei women also shouldered the

burden of gender norms from Japan in the US. Though far from home, Japanese

women were still expected to fulfill the expectations of being dutiful mothers

and wives.[26] Despite the cultural pressures, American ideas and customs regarding women

surprised Japanese women. Women in Japan were taught Confucian-based ideals of duty

and unquestioned obedience to husbands, distinctly clashing with the more elevated

perceptions held by Americans. One Issei woman recalled, “I had a surprise one

day when I was packing strawberries. I comb fell from my hair, and a Caucasian

man picked it up for me. In Japan a man would never do that. I was so

impressed!” While life for Issei women was difficult, their presence was

supremely important to the presence of Japanese in the US. Because of the

additional labor Issei women provided on top of companionship and motherhood,

scholars have cited them as a key factor in the creation of permanent Japanese

communities.[27] Though

the sacrifices and tireless work of Issei women helped to secure a foothold in

America, nativists were working ceaselessly to evict them.

|

| Fig. 6: Five Issei women, picture likely taken in Seattle. Densho Digital Repository |

With the dawning of the 1920’s also came a revitalized exclusion movement, seeking to expand on previous victories like the 1907 Gentlemen’s Agreement. Though Japanese immigration was curbed, anti-Japanese groups sought not only to close immigration entirely but to also eliminate the ability for Japanese immigrants to own land. As it had been many times before, California and its powerful exclusionist organizations inspired similar movements in the Pacific Northwest. Bills excluding Japanese from owning land were constantly being introduced following 1907, with California eventually passing such a bill in 1913. With California leading the way with its own victory, states in the Pacific Northwest eagerly followed the example set. In spite of pro-Japanese opposition groups, the Alien Land Law passed in Washington in 1921 before Oregon followed suit in 1923.[28] The passage of exclusionary land laws was not a phenomenon limited to the West Coast as Idaho passed its own legislation in 1923. By 1925, five other states, including those as far-flung as Kansas and Louisiana, passed similar land laws.[29] Though the passage of land laws was an important goal for the anti-Japanese movement, larger goals still lay ahead for exclusionists. In the midst of the campaign for land laws, pressure from the United States resulted in Japan ending the migration of “picture brides” in 1920. Despite this, thousands of Japanese women already successfully immigrated and set up the next generation of Japanese Americans.[30] Nevertheless, exclusionists mustered their momentum to pursue the goal they had long dreamed, completely ending immigration from Japan.

The 1907 Gentlemen’s Agreement had been a notable success for the exclusion movement, but it was not the complete victory that many had hoped for. The compromise shut off immigration for laborers, though different classes such as merchants, students, and others were unaffected by the legislation. With the continued Japanese migration to the United States, exclusionists in 1924 made their attempt to expand upon the Gentlemen’s Agreement further, shutting off the remaining avenues for immigration. Though exclusion was a powerful movement that had been continuously successful in the years leading up, Japan’s acquiescence to demands made by the United States as well as pro-immigration organizations and politicians proved to be a formidable bulwark against it. While the pro-immigration side had made a concerted effort during Senate hearings, political support and favorable events tipped in the odds for exclusion. Japanese Ambassador Masanao Hinahara angrily protested the potential for an expansion to exclusion policies, warning of “grave consequences” for Japan-US relations. This threat rallied nationalist sentiment in the US, prompting Senators to vote for what became the Immigration Act of 1924. Further Japanese exclusion, which was conveniently attached in a package of reforms for the Immigration Act, was signed into law by President Calvin Coolidge.[31] Though the Immigration Act of 1924 was a crowning achievement for the exclusionist movement, their victory over Japanese in the United States was far from total. The Issei had already arrived in number, made the United States their home, and produced the next generation of Japanese Americans, the Nisei. As exclusionists turned their attention to other groups, the Issei continued to live quietly in the America throughout the 1920’s and 1930’s. Though they enjoyed a modicum of peace in the following years, events on December 7, 1941 rekindled anti-Japanese sentiments to an unprecedented level.

Returning Home and Conclusion

|

| Fig. 7: A racial epithet written on a garage door, likely written during the resettlement of Japanese Americans in 1945. Densho Digital Repository |

With war declared after the attack on Pearl Harbor, questions were immediately raised regarding the presence of Japanese Americans on the West Coast. On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 into law, leading to the incarceration of 120,000 Japanese Americans, Issei and Nisei alike. Despite the war quickly turning in favor of the United States, many Japanese Americans remained in incarceration camps until 1945. While incarceration was a deeply distressful and scarring experience, many Issei sought to return to their former homes after they were released from the camps. Despite the hysteria of an impending Japanese invasion being a distant memory, many Japanese upon returning to their homes were greeted by old neighbors who vigorously opposed their return to the community. Hood River, Oregon was one of the most infamous examples of this discrimination as the local American Legion Post campaigned intensely to prevent the return of the Japanese. The Post became the center of national scrutiny after it was revealed that the names of sixteen Japanese American soldiers were erased from a war memorial. With the all-Japanese 442nd Regimental Combat Team earning fame for its storied performance during the war, the actions of the American Legion were nationally condemned rather than accepted as they were in the past.[32] With the end of the war came a long hoped for opportunity, the chance at earning citizenship. After decades of being shut off from the possibility of becoming Americans and suffering for being regarded as “aliens,” the United States relented from its position of exclusion. In 1952, the McCarran-Walter Act was passed to officially grant Japanese eligibility for citizenship, a right that was eagerly taken up by many. Iyo Tsutsui, who had been incarcerated at the Manzanar, expressed her feelings regarding the opportunity saying, “I had dedicated to have my bones buried here a long time ago, so I really wanted to get my citizenship.”[33] While citizenship might make up for decades of waiting, some had bittersweet reflections as some losses were never recovered. Ko Haji’s only son served with the 442nd during the war and was killed in action a little less than a month before the end of the conflict. She reflected, “Losing my only son was a great sadness to me. This was the son who was to carry on the family name. But I don’t regret coming to America, people are sympathetic that I lost my only son, but I am proud of him because he served his country and he is remembered for that.”[34]

The Japanese experience in the

United States is oftentimes focused on the accomplishments and activism by the

Nisei generation, and it is understandable why this is the case. Many Nisei epitomized

Americanism within Japanese communities and thousands eagerly proved their

patriotism on the battlefields of World War II. This outstanding conduct not

only won over many skeptical Americans, it greatly assisted with future

legislative victories. From the McCarren-Walter Act to the Redress Movement in

the 1980’s, Nisei championed better lives for future generations. While the

accomplishments of the Nisei are impressive, the contributions of the Issei

generation should also be regarded highly. The Issei arrived into the United States

with little more than the hope of making a better future, oftentimes discovering

this land of plenty to be filled with harsh living and discrimination. As Asian

immigrants the Issei were prevented from acquiring citizenship, a condition

that rendered severely hindered them against exclusionist legislation that was

devoted to their removal from the United States. In spite of the overwhelming

challenges that came with life in America, thousands of Issei found life and

opportunities inviting enough to persevere. Despite suffering through withering

amounts of discrimination, the Issei were not simply helpless victims. They had

a dedication to survival and were to find spaces while dealing with the worst

of the exclusionist movement. Through hard work, communal support, and the

desire to provide a better future, the Issei were able to create a foundation

within the United States for future generations to change the nation. With an increased focus on the struggles of Asian Americans in the United States, the story of the Issei is an example of how importance persistence in the face of discrimination and a commitment to justice can be.

About the Historian: MJ Vega is a second-year Master's student studying Public History under Orlan Svingen.

Born and raised in Washington, MJ graduated from Washington State

University in 2018 with a B.A. in History. He returned to WSU in 2019,

where he studies the experiences of Japanese Americans on the Palouse during World War II and the development of Americanism in Nisei and rural communities. In his free time, MJ runs a website dedicated to the history of his high school football team and also makes short videos on historical topics. He also enjoys listening to music, going

to local coffee shops, and exploring the Palouse.

Sources

[1] Shelley Sang-Hee Lee, Claiming the Oriental Gateway: Prewar Seattle and Japanese America. (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2011.) 31.

[2] Thomas H. Heuterman, The Burning Horse: Japanese-American Experience in the Yakima Valley, 1921-1942. (Cheney, WA: Eastern Washington University Press, 1995.), 3-4.

[3] Kazuo Ito, Issei: A History of Japanese Immigrants in North America. (Seattle: Japanese Community Service, 1973.), 5-7.

[4] Ito, Issei, 14-15.

[5] Roger Daniels, The Politics of Prejudice: The Anti-Japanese Movement in California and the Struggle for Japanese Exclusion. (Berkley: University of California Press, 1962.), 1.

[6] Louis Fiset and Gail M. Nomura. Nikkei in the Pacific Northwest: Japanese Americans & Japanese Canadians in the Twentieth Century. (Seattle: Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest in association with University of Washington Press, 2005.), 5.

[7] Ito, Issei, 17-19.

[8] Heuterman, The Burning Horse, 5.

[9] Eileen Sunada Sarasohn, Issei Women: Echoes from Another Frontier. (Palo Alto: Pacific Books, 1998.) 69-71.

[10] Ito, Issei, 4-5.

[11] Robert K. Fitts, Issei Baseball: The Story of the First Japanese American Ballplayers. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2020.), 70-71.

[12] Ronald T. Takaki, Strangers from a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans. (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1998.), 201-203.

[13] Linda Tamura, The Hood River Issei: An Oral History of Japanese Settlers in Oregon's Hood River Valley. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993.), 22.

[14] Ito, Issei, 91.

[15] "Snohomish Valley Threatened by Japs", Monroe Monitor-Transcript. April 21, 1911.

[16] "A Japanese of Palouse Makes Sausage of Lumber Jack", The Colfax Gazette, June 14, 1907.

[17] Masakazu Iwata, Planted in Good Soil: A History of the Issei in the United States Agriculture. (New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 1992.), 125-126.

[18] Ito, Issei, 110-117.

[19] Ito, Issei, 124-125.

[20] Tamura, The Hood River Issei, 88-89.

[21] Heuterman, The Burning Horse, 18-19.

[22] Tamura, The Hood River Issei, 50-52.

[23] Heuterman, The Burning Horse, 36-37.

[24] Citizens of Idaho, Shall Japanese-Americans in Idaho be Treated with Fairness and Justice or Not? (Boise, Idaho, 1921.), 2-4.

[25] Tamura, The Hood River Issei, 53-55.

[26] Sarasohn, Issei Women, 90.

[27] Tamura, The Hood River Issei, 97-98.

[28] Ito, Issei, 157-159.

[29] Dudley O. McGovney. "The Anti-Japanese Land Laws of California and Ten Other States." California Law Review 35, no. 1 (1947): 7-8. https://doi.org/10.2307/3477374.

[30] Lee, Claiming the Oriental Gateway, 31-32.

[31] Lon Kurashige, Two Faces of Exclusion: The Untold History of Anti-Asian Racism in the United States, (Chapel Holl: The University of North Carolina Press, 2016.), 134-137.

[32] Tamura, The Hood River Issei, 215-219

[33] Sarasohn, Issei Women, 203-206.

[34] Ibid, 188-189.

Comments

Post a Comment