How Annette Gordon-Reed Retold the Story of Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson

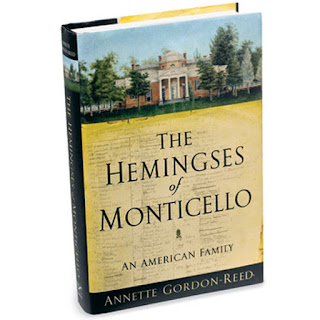

In the preface to her 2008 book, The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family, Annette Gordon-Reed argues that the titular family provide ideal subjects through which to view slave life because they “escaped the enforced anonymity of slavery” due to several reasons, among them being their ownership by a well-known historical figure; their existence at Monticello itself (a house that was built and maintained by the Hemingses); and the public knowledge of Thomas Jefferson’s sexual relationship with Sally Hemings during the time period it actually occurred.[1]

In addition, the Hemingses were able to “achieve and maintain a coherent family identity that existed within slavery and survived it.”[2] The Hemingses of Monticello is breathtaking in scope, covering the lives of three generations of a slave family connected in both proximity and blood to arguably the most legendary of American founders.

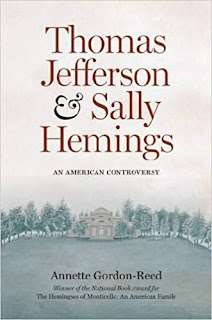

However, up until Gordon-Reed’s publication of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: An American Controversy in 1997, historians of Jefferson refuted the suggestion he had a nearly four-decade sexual relationship with Hemings, producing seven children, four of whom lived to adulthood. Much of these arguments were presented without any considerable effort given to examining in detail the circumstantial evidence available in the archives, nor did they take seriously the oral history of someone who knew both parties: that of Madison Hemings, Sally's son with Jefferson.

Gordon-Reed’s purpose in writing Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings was not so much to prove Jefferson fathered Hemings’ children but rather to review the evidence in its entirety. The author’s legal background provides a methodological framework she utilizes throughout, beginning with her re-examination of The Memoirs of Madison Hemings. She interrogates the work of historians such as Dumas Malone, offering critical questions about paths left unexplored as scholars sought to establish plausible deniability, above all else, where Jefferson was concerned. With Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, Gordon-Reed highlights the humanity of the Hemings family and provides an opportunity for them to tell their story.

Gordon-Reed’s 1997 book is organized into separate chapters, in which figures central to the Jefferson/Hemings story are introduced, and archival material previously examined by other historians is given a methodical reevaluation. In Chapter One, Gordon-Reed builds a case of plausible doubt about previous historians’ interpretations of Madison Hemings’ statement regarding his parentage. Most profound is her declaration that Hemings’ claim was not taken seriously, or worse, met with derision, because historians could not conceive of slaves as human beings.[3]

It never dawned on them, or they chose not to explore, the idea that Madison and Sally Hemings experienced the “normal processes of communication and love between mother and child” because they “existed only in relation to their servitude, as mere props in the real story of slave masters and their lives.”[4] After her case is built, Gordon-Reed then re-examines Madison Hemings’ statement without reliance on stereotypes and superficiality, presenting a more fully realized and nuanced take on his memoirs.

In Chapter Two, Gordon-Reed examines the public allegations made by James Callender during Thomas Jefferson’s presidency. The disagreeable nature of Callender’s character lent itself to discrediting much of what he accused Jefferson of by later historians. However, Gordon-Reed reveals the complexities of the relationship between Callender and Jefferson as she asks the serious question: “Does having a motive for telling a story mean that the story is false?”[5]

Gordon-Reed moves the focus away from Callender’s potential misidentification of one of Sally Hemings’ children as proof that Jefferson did not father her children and toward the idea that it had been much more convenient to “render Callender meaningless” rather than explore the potential elements of truth in what he wrote.[6]

Chapter Three looks at the past promotion of Thomas Jefferson’s nephews, Samuel and Peter Carr, as the potential fathers of Sally Hemings’ children. Gordon-Reed cross-examines the opinion offered by Jefferson’s grandchildren, T.J. Randolph and Ellen Randolph Coolidge, about who fathered Hemings’ children. Their declaration that it must have been one of the Carrs was embraced by past historians who wanted it to be so, without analysis or in-depth investigation, because someone had to be the father—and they preferred to have a named culprit. As Gordon-Reed notes, all normal standards for judging evidence have “been abrogated,” with the Carrs inhabiting historical roles as “human shields to protect the man who personified America."[7]

source: Wikipedia

Historians’ defense of Jefferson’s moral character as reason enough to believe he never engaged in a sexual relationship with Sally Hemings is the central debate of Chapter Four. Gordon-Reed examines the motivations of historians who never considered the validity of Madison Hemings’ tale, because to do so would acknowledge that Sally Hemings, an enslaved woman, likely knew Thomas Jefferson better than anyone.

In addition, given his almost obsessive interest in his acknowledged daughters, the idea that Jefferson would treat his children by Hemings with indifference contrasts so markedly from the man prior historians “knew” him to be. Such intellectual laziness served to deny the humanity due the Hemingses for far too long.

Gordon-Reed uses Chapter Five to interrogate the enigma of Sally Hemings as well as reconstruct the details of her life, giving voice to the enigmatic character so easily dismissed in earlier scholarship about Jefferson. When writing about Sally Hemings, Gordon-Reed must rely on observations from everyone but Sally herself. She effectively recreates the slave hierarchy of Monticello and not only provides valuable insight about Sally’s place within it but also sheds light on the preferential treatment her family received. Gordon-Reed’s legal background serves her well in her interrogation of prior historians’ work, and she offers a thorough re-examination of sources that are not new. She leaves no stone unturned, and her scholarship is admirable.

source: CBS

One area lacking is her examination of race in early America, as well as her omission of a detailed analysis of the patriarchal structure of the colonial planter class of which Jefferson was a societal leader. This lack of analysis leaves some wiggle room for historians who insist Jefferson’s racism would have precluded a sexual relationship with his slave.

In fact, colonial laws prioritized the needs of slaveholders by treating women as capital, thus exposing enslaved women to sexual exploitation and a lack of bodily autonomy. Colonial laws essentially excluded rape as a possibility for enslaved women, thus ensuring sexual violence as a means to propagate slavery.

This does not discount the importance of Gordon-Reed’s work. With Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, Gordon-Reed effectively challenged and overturned nearly two centuries of scholarship centered on the protection of Jefferson’s infallible character to offer a much more complex narrative of blended families bound by the original sin of slavery.

About the author: Samantha Edgerton is a first-year doctoral student working with Dr. Laurie Mercier. Her primary research fields are women and gender, race and ethnicity, social movements, and popular culture in the twentieth-century United States. Her Master’s thesis—"Better Than Being on the Streets": Oregon, Idaho, and the Battered Women’s Movement—centered on interpersonal violence (IPV) and the battered women’s shelter movement in Oregon and Idaho from 1975-1994.

[1] Annette Gordon-Reed, The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family (W.W. Norton & Company, 2008), Kindle location, 24-25.

[2] Ibid., Kindle location, 28.

[3] Gordon-Reed, Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, Kindle edition, location 766.

[4] Ibid., Kindle edition, locations 766, 770.

[5] Ibid., Kindle edition, location 1633.

[6] Ibid., Kindle edition, location 1943.

[7] Ibid., Kindle edition, location 2016.

Comments

Post a Comment