Placing the American Civil War in an International Context

Whether perusing high school history textbooks or viewing documentary films by Ken Burns, one is left impressed by the sheer magnitude of the American Civil War. In fact, few other phenomena can be said to have exerted so dramatic an influence on the United States as a nation. More than 150 years later the events during that period have become mythologized into a canon of oft-repeated tales about noble leaders and heroic battles. Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis ... Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee ... Gettysburg and Antietam.

source: New York Public Library

Myriad other names and locations have been immortalized in the historical memory of Americans as well. In many of these narratives the United States nation, both united and divided, remains the central player within this historical narrative.[1] In many respects this nation-centric focus is understandable. Although too diverse and far-reaching to sufficiently examine in this space, the Civil War helped to create and propel dramatic social, cultural, economic, and political changes that continue to shape the United States today.[2]

It is nevertheless worth stepping back for a moment to examine the United States within the broader international context. The United States was, of course, not the only nation in the world during this period of American history, nor even the only nation whose interests were connected to the outcome of the Civil War. In fact, the Confederate States of America were counting on this to survive. Persuading other countries to officially recognize the Confederacy as an independent nation was the central theme of Southern diplomacy. This would not only help legitimize their declaration of independence but would enable them to apply for loans, sign treaties, and form alliances. In a best-case scenario this would even entail direct foreign military intervention on behalf of the Confederacy.[3] Rather than dealing with the volatile issue of slavery, Confederate diplomats argued that they were fighting for “national self-determination and free trade.”[4]

The Lincoln Administration was faced with a similar struggle to justify its cause internationally and desperately attempted to prevent foreign intervention. Warning European countries that any formal diplomatic recognition of the Confederacy would be considered a declaration of war, Secretary of State William Seward announced that the United States was willing to “wrap the whole world in flames.”[5] However, Seward also cautioned the Union against provoking foreign powers by taking action against slavery that would destabilize the cotton market. Lincoln himself chose to frame the cause for war around the legality of succession rather than slavery, seeking to counter concerns that the war would bring abolition and to undermine the Confederacy’s justification for seeking independence.[6]

The Union and Confederacy both competed for international public opinion, enlisting diplomats and foreign nationals to promote their respective foreign policy objectives in what historian Don Doyle argues was the first official pursuit of “public diplomacy.”[7] Confederate efforts were not predetermined to fail.[8] Their message initially resonated with the European aristocrats and conservatives who saw the Civil War as proof of the failure of republicanism. During the first half of the nineteenth century, Europe had been wracked by revolts against the established monarchies by publics eager for greater political freedoms. It was hoped that the collapse of the United States would weaken the international appeal of republicanism and further solidify established power.[9]

The political leadership in Great Britain was divided over the prospect of supporting the Confederacy. Politicians like Prime Minister Henry John Temple disapproved of slavery but felt that the broad enfranchisement promoted by American democracy sewed discontent in Britain, threatening the balance achieved through British constitutional monarchy. Britain toyed with the idea of recognizing the Confederacy, although it remained reluctant to risk a direct conflict with the Union.[10]

source: Wikipedia Commons

This conflict seemed inevitable for a tense several weeks at the end of 1961 when the Union Navy boarded the British vessel Trent to detain two Confederate diplomats. Angry at the breach of sovereignty, British policymakers and the press pushed for war. In response, the Union was forced to rely on both official and unofficial diplomatic channels to avoid an escalation of tensions. Informal diplomats such as Seward’s assistant Thurlow Weed were sent abroad to mollify British opinion, and the release of the two detained diplomats that January successfully nullified Britain’s cause for war.[11] However, it is impossible to tell what would have happened if these tensions had continued to escalate, or how the Civil War would have concluded had Britain joined the war against the Union.

France was another important European actor during this period, and one that seemed likely to support the Confederacy. With the United States weakened and wracked by internal conflict, King Napoleon III sought to pursue a “Grand Design,” an ambitious and grossly optimistic plan to remake South America and parts of North America into a network of Catholic monarchies led by France.[12]

source: Wikipedia Commons

Seeking to initiate this plan by reestablishing monarchical rule in Mexico, France unilaterally waged war against the republican government of Benito Juárez. Napoleon III’s plans were temporarily halted when French forces were defeated by the Mexican army on May 5, 1862, a victory commemorated today as Cinco de Mayo. Although France eventually succeeded in conquering Mexico and briefly installing Austrian Emperor Maximilian, this costly delay gave the Union time to gain international support for their cause while turning the French mood against intervention. Together these factors helped ensured that it was politically unfeasible for the French government to openly side with the Confederacy.[13]

This shift accelerated as the Civil War progressed, and the Union slowly gained ground in the battle for public opinion. Politicians such as Confederate President Jefferson Davis had confidently believed that instead of begging for assistance from Europe, European dependence on Southern cotton would be enough to convince countries such as Britain and France to support the Confederacy.[14] The Confederacy’s diplomatic leverage was weakened, however, when the self-imposed embargo on cotton they implemented to increase pressure on industrialized European nations failed to illicit the desired support. Many of these governments such as Britain and France chose instead to acquire cotton through smuggling routes and from overseas colonial possessions.[15]

The Union also benefited due to its ability to draw upon popular support from a European public eager for greater political and social freedoms. Despite the Lincoln Administration's reluctance to engage in a war of emancipation, numerous “foreign politicians, journalists, and intellectuals … reached their own conclusions” about the ideological “principles at stake” in the outcome of the Civil War.[16]

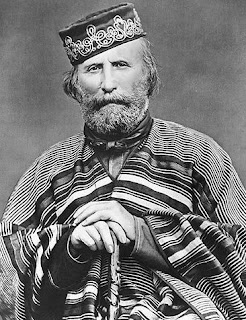

Many of these foreign nationals explicitly connected the Civil War to slavery, despite Union statements to the contrary. Even Karl Marx picked up his pen in support for the Union, believing the destruction of Southern slavery a necessary step to promote “the system of free labor.”[17] The chance imprisonment of the popular Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Garibaldi in 1862 and his subsequent “endorsement of the Union cause” helped initiate a wave of “popular support” for the United States across Europe.[18]

source: Wikipedia Commons

It was this quest for foreign public support that helped prompt Lincoln to sign the Emancipation Proclamation in late 1862. Seeking to clarify the Union’s ideological and moral justifications for war while appealing to anti-slavery sentiment abroad, Lincoln’s action helped to tilt foreign public opinion decisively in favor of the Union, removing any possibility that Britain and France would either military or diplomatically intervene in support for the Confederacy.[19]

The Union also reaped tangible military benefits from the support of the foreign public in the form of immigration. Although many immigrants entered the United States before the war, once fighting commenced many more crossed the Atlantic to fight for the Union. Some were attracted by the promise of land, facilitated by the Homestead Act of 1862 that promised land to new immigrants. In fact, the Union covertly publicized this offer overseas in technical violation of laws prohibiting the solicitation of recruits in neutral countries.

Still others were drawn by ideology, seeing the war as a continuation of the struggles for freedom they had fought at home. Many had previous military experience, and all helped the Union replace losses sustained during the fighting. This much needed pool of manpower also took pressure off of voting Americans to serve, granting Lincoln greater political freedom to continue waging war against the Confederacy. All told, hundreds of thousands of immigrants and their immediate decedents served for the Union, comprising roughly “43 percent of all Union armed forces.”[20]

This post only touches upon the many diverse international and transnational relationships that infused the American Civil War. However, examining national events within an international scope can help illustrate the true scale and complexity of seemingly localized phenomena.

During the Civil War French Professor Édouard de Laboulaye was a prominent supporter of both republicanism and the United States. He was also a friend to architect Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi. In fact, the discussion the two participated in at an 1865 dinner party honoring the late President Lincoln and the Union victory has been credited with inspiring Bartholdi to construct the statue “Liberty Enlightening the World.”

source: New York Public Library

The details of this party have been questioned, and it may be apocryphal. However, when examining the symbolism within the Statue of Liberty, it is significant to reflect on the fact that, as Doyle writes, “Liberty faces Europe and is striding toward it while at her feet [lie] the broken chains of slavery.”[21] In this interpretation the Statue of Liberty does not passively stand, but is depicted as actively spreading the principles of American democracy to the oppressed peoples of the world.

At the very least, this demonstrates how the American Civil War was conducted, not as an isolated conflict in distant lands but within an international arena. The moral and ideological imperatives perceived to be at stake in the outcome were not confined to the United States yet instead represented transnational concepts of republicanism and liberty shared, held dear by revolutionaries around the world.

About the author: James Schroeder is a doctoral student working under Dr. Noriko Kawamura. His research interest focuses on the military history and foreign relations of the United States in the twentieth century. James enjoys traveling, reading, and drinking coffee.

[1] Don Harrison Doyle, The Cause of All Nations: An International History of the American Civil War (New York: Basic Books, 2015), 11.

[2] Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008), xiii, xvii-xviii.

[3] Doyle, 27-28.

[4] Doyle, 29, 143.

[5] Doyle, 50-51.

[6] Doyle, 6, 54-55, 67, 70, 210-212.

[7] Doyle, 3-4.

[8] Doyle, 4-5.

[9] Doyle, 8, 85-86, 91-96.

[10] Francis M. Carroll, “The American Civil War and British Intervention: The Threat of Anglo-American Conflict,” Canadian Journal of History 47, no. 1 (2012): 90-93; Doyle, 41-42.

[11] Doyle, 46-48, 63, 73, 76-81.

[12] Doyle, 8, 107-109.

[13] Doyle, 116-117, 123-126, 128, 226, 233-237, 259-260, 305.

[14] Doyle, 38-39.

[15] Brian Schoen, The Fragile Fabric of Union: Cotton, Federal Politics, and the Global Origins of the Civil War (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), 266-267.

[16] Doyle, 6-8, 131-133.

[17] Doyle, 3-4, 6, 82, 131-133, 138-141, 150-153.

[18] Doyle, 225-234.

[19] Doyle, 210-216, 241-245, 249, 256.

[20] Doyle, 158-160, 167, 170, 173, 176-177, 180-181.

[21] Edward Berenson, The Statue of Liberty a Transatlantic Story (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), 9-10; Doyle, 138-142, 311-313.

Comments

Post a Comment